IFRS Business Combinations Standard A Deep Dive

IFRS business combinations standard Artikels the rules for accounting when one company acquires another. Understanding this complex framework is crucial for accurate financial reporting in mergers and acquisitions. This guide delves into the key principles, practical applications, and recent updates of this standard, offering a clear and comprehensive overview.

The standard, encompassing various aspects from identifying acquisition costs to consolidating financial statements, provides a structured approach for recognizing and reporting the value of a business combination. It’s a cornerstone of international financial reporting, ensuring comparability and transparency across different jurisdictions.

Introduction to IFRS Business Combinations Standard

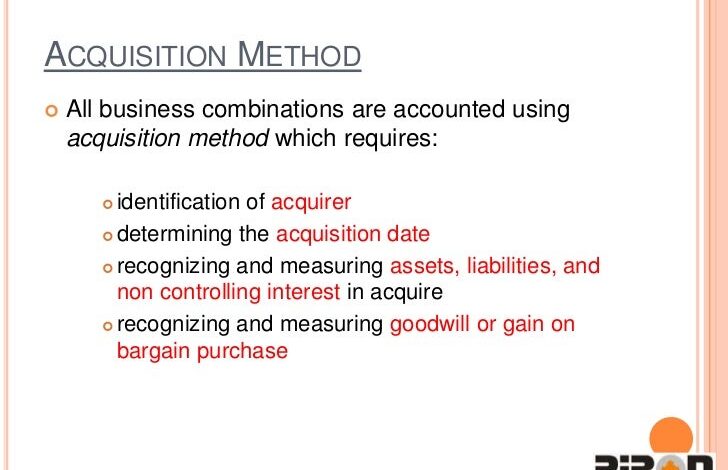

The IFRS Business Combinations Standard, formally known as IFRS 3, dictates how businesses should account for the acquisition of another business. It provides a framework for recognizing and measuring the assets, liabilities, and contingent liabilities acquired in a business combination, ensuring consistent and comparable financial reporting across companies. This standard is crucial for investors, creditors, and other stakeholders to understand the true financial position and performance of an acquiring entity.

Core Principles and Objectives

The core principle of IFRS 3 is to recognize the identifiable net assets acquired and the non-controlling interest (NCI) at the acquisition date. This ensures that the acquirer accurately reflects the fair value of the acquired entity on its financial statements. The objective is to present a complete and accurate picture of the combined entity, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions.

This includes considering the fair value of all assets and liabilities involved in the transaction, including intangible assets. The standard aims to minimize accounting distortions that could arise from different acquisition methods.

Historical Context and Evolution

The IFRS Business Combinations Standard has undergone revisions over time to enhance its clarity and address evolving accounting practices. The initial version of IFRS 3 was published and used for some time. Significant changes have been implemented over the years to address accounting issues and concerns. The standard has adapted to accommodate the complexity of modern business acquisitions, particularly those involving intangible assets, goodwill, and non-controlling interests.

This evolution reflects the ongoing effort to maintain the standard’s relevance in a dynamic business environment.

Key Changes Over Time, Ifrs business combinations standard

| Standard Name | Effective Date | Key Changes |

|---|---|---|

| IFRS 3 (2004) | 1 January 2005 | Established the initial framework for business combinations, emphasizing fair value measurement. |

| Amendments to IFRS 3 (2010) | 1 January 2012 | Clarified the accounting treatment for certain assets and liabilities, including intangible assets and contingent liabilities, particularly for acquisitions involving share exchanges and cash payments. This aimed to reduce ambiguities in the previous standard. |

| Amendments to IFRS 3 (2014) | 1 January 2015 | Introduced changes to address the recognition of deferred tax liabilities and assets arising from the acquisition of an entity. This enhanced the accuracy of tax accounting. |

| IFRS 3 (as amended) | Current Standard | The current standard includes all amendments and clarifications, providing a comprehensive framework for accounting for business combinations. |

Identifying and Measuring Acquisition Costs

The IFRS Business Combinations standard meticulously Artikels the process of identifying and measuring acquisition costs. This crucial step ensures accurate reflection of the value acquired in a business combination, influencing the financial statements and providing a true and fair view of the transaction. Understanding the various components and their accounting treatment is essential for proper reporting and analysis.

Components of Acquisition Costs

Acquisition costs encompass all expenditures directly attributable to the acquisition. These are not limited to the purchase price but include other necessary expenses. These costs are essential to determine the overall cost of acquiring the target entity.

- Purchase Price: This includes the cash paid, the fair value of any non-cash assets transferred, and the fair value of any liabilities assumed by the acquirer.

- Acquisition-related Costs: These encompass expenses directly associated with the acquisition, such as legal fees, accounting fees, and brokerage commissions. These are often incurred to facilitate the process.

- Transaction Costs: This includes all costs associated with the transaction, such as fees paid to advisors, consultants, and other intermediaries.

- Costs of Integrating the Acquired Business: These are expenditures directly related to integrating the acquired business into the acquirer’s operations, such as restructuring costs and employee severance costs. These are recognized when the acquirer incurs them, not when the transaction is completed.

Accounting Treatment of Acquisition Costs

The accounting treatment of acquisition costs is critical for accurately reflecting the value of the acquisition. All directly attributable costs are included in the acquisition cost, and any indirect costs are excluded.

- Purchase Price: The purchase price is measured at fair value on the acquisition date. This might involve complex valuation techniques, particularly for intangible assets.

- Acquisition-related Costs: These costs are expensed as incurred, in accordance with the principle of recognizing expenses in the period they are incurred.

- Transaction Costs: Similar to acquisition-related costs, transaction costs are expensed as incurred.

- Costs of Integrating the Acquired Business: These costs are recognized as expenses when incurred, not capitalized.

Contingent Consideration

Contingent consideration represents a payment or transfer of assets that is dependent on a future event. Its measurement is often challenging due to the uncertainty surrounding the future event.

- Measurement of Contingent Consideration: Contingent consideration is measured at fair value on the acquisition date. The fair value is often estimated using probability-weighted expected values, and the effect of any variability is considered.

- Examples: A contingent consideration might be a performance-based payment or a contingent liability. The acquirer estimates the probability of the contingent consideration occurring and its value based on various factors, including historical data, market conditions, and expert assessments.

Comparison of Acquisition Cost Components

| Acquisition Cost Component | Accounting Treatment |

|---|---|

| Purchase Price | Measured at fair value on the acquisition date. |

| Acquisition-related Costs | Expensed as incurred. |

| Transaction Costs | Expensed as incurred. |

| Costs of Integrating the Acquired Business | Expensed as incurred. |

| Contingent Consideration | Measured at fair value on the acquisition date. |

Assessing Control over an Entity

Understanding control is paramount in applying the IFRS Business Combinations standard. It’s not simply about owning a majority of shares; rather, it’s about the power to direct the activities of the entity. This involves influencing the entity’s financial and operating policies. This section delves into the intricacies of control, providing examples and a structured method for analysis.The definition of control within the context of business combinations hinges on the ability to affect the entity’s economic returns.

This influence extends beyond simple voting rights; it encompasses the power to govern the entity’s activities and ultimately, its financial performance. Crucially, this influence needs to be significant, enabling the acquirer to affect the entity’s economic returns.

Definition of Control

Control over an entity in a business combination is the power to direct the relevant activities of the entity. This includes influencing the entity’s financial and operating policies to achieve the acquirer’s objectives.

Indicators of Control

Various indicators suggest the presence or absence of control. These factors often overlap and must be considered collectively.

- Significant Influence vs. Control: A key distinction lies in the level of influence. Significant influence suggests some impact on the entity’s policies, but not the dominant power to direct the entity. In contrast, control implies the ability to dictate the entity’s overall strategy and economic performance.

- Voting Rights and Equity Interests: While ownership of a majority of voting shares often indicates control, other factors like contractual agreements or the structure of the entity’s governance can influence this. Consider cases where a minority shareholder holds a significant amount of voting power through a complex agreement or where significant assets are under the control of a separate entity.

The focus is on the overall power to direct the entity, not solely on ownership percentage.

- Contractual Agreements: Agreements granting the acquirer the right to direct the entity’s operations, such as management contracts or agreements specifying voting rights, can be indicators of control.

- Economic Returns: The ability to affect the entity’s economic returns is a crucial indicator. This involves influencing the entity’s financial policies, operational strategies, and ultimately, its profitability.

- Governance Structure: The structure of the entity’s governance and decision-making processes should be evaluated. Does the acquirer have the ability to shape the entity’s strategy and policy through board representation or other means? The existence of interlocking directorates, for example, may be an indicator of control.

Methods to Analyze Control

A structured approach to analyzing control is essential for accurate application of IFRS standards. Here’s a suggested method:

- Identify the relevant activities of the entity: Begin by pinpointing the core activities of the acquired entity that generate economic returns. This includes production, sales, and other key operations.

- Assess the acquirer’s power to direct those activities: Analyze the extent to which the acquirer can influence the entity’s policies and operational decisions related to these key activities. Consider legal documents, board representation, and any other contractual arrangements.

- Evaluate the influence on economic returns: Determine the acquirer’s ability to influence the entity’s profitability, cash flows, and other key financial performance indicators. Assess if the acquirer has the power to affect the entity’s overall economic outcome.

- Consider all relevant factors: Combine the results of steps one through three with other indicators, such as voting rights, equity interests, and contractual agreements, to reach a comprehensive conclusion.

- Document the findings: Thoroughly document the analysis process and the rationale for the conclusion. This is critical for audit trails and transparency.

Examples

| Situation | Control Present? | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Acquirer owns 80% of the voting shares and has representation on the board of directors. | Yes | High ownership percentage and board representation demonstrate significant influence and control. |

| Acquirer has a management contract that allows them to direct the entity’s operations. | Yes | The contract grants the acquirer the ability to make operational decisions and thus control the entity. |

| Acquirer owns a minority stake but holds a significant share of the entity’s key assets through a separate entity. | Possibly | The combined influence must be assessed holistically to determine if control is present. |

| Acquirer has a significant influence on the entity’s policies, but lacks the power to direct its operations. | No | Significant influence does not equate to control. |

Accounting for Intangible Assets Acquired: Ifrs Business Combinations Standard

The IFRS Business Combinations standard mandates a specific treatment for intangible assets acquired in a business combination. Understanding this treatment is crucial for accurately reflecting the value of the acquired entity in the acquirer’s financial statements. This involves more than just recognizing the asset; the method of amortization also plays a significant role.Acquired intangible assets are not always immediately obvious in a financial statement.

Often, they represent valuable, yet often unseen, aspects of a business, such as brand recognition, customer relationships, or intellectual property. Correctly accounting for these assets is vital for a fair valuation of the acquisition.

Treatment of Acquired Intangible Assets

The standard requires that acquired intangible assets be recognized at their fair value at the acquisition date. This fair value is typically determined by an independent valuation process or by reference to comparable market transactions. Subsequently, the acquirer needs to assess if the intangible asset is separable or arises from contractual or other legal rights.

Types of Intangible Assets and Their Accounting

Various types of intangible assets can be acquired, each with its own accounting implications. Common examples include trademarks, patents, copyrights, customer relationships, and brand names. These assets may have varying useful lives, impacting their amortization periods. The acquisition of a company often includes a collection of intangible assets that must be assessed individually for proper recognition and accounting treatment.

Amortization Policies for Intangible Assets

Amortization is the systematic allocation of the cost of an intangible asset over its estimated useful life. The useful life is the period over which the asset is expected to contribute to the acquirer’s operations. Intangible assets with indefinite lives are not amortized. Instead, they are subject to impairment testing annually.

Table of Intangible Asset Accounting

| Intangible Asset Type | Recognition | Amortization |

|---|---|---|

| Patents | Recognized at fair value. | Amortized over the shorter of the legal life or the estimated useful life. |

| Trademarks | Recognized at fair value. | Generally, not amortized. Subject to impairment testing if there’s evidence of impairment. |

| Copyrights | Recognized at fair value. | Amortized over the shorter of the legal life or the estimated useful life. |

| Customer Relationships | Recognized at fair value, if separable and the future economic benefits are probable. | Amortized over the estimated useful life, or tested for impairment. |

| Brand Names | Recognized at fair value. | Generally, not amortized. Subject to impairment testing if there’s evidence of impairment. |

Important note: The specifics of amortization and impairment testing depend heavily on the individual circumstances of the acquisition and the characteristics of the intangible assets. Consult with financial professionals for guidance tailored to particular situations.

Goodwill and Impairment

A crucial aspect of accounting for business combinations is understanding goodwill and its potential impairment. Goodwill arises when the purchase price of an acquired entity exceeds the fair value of its identifiable net assets. This excess is recognized as goodwill on the balance sheet. However, this asset isn’t permanent; it’s subject to periodic impairment testing to ensure its carrying amount reflects its recoverable amount.

Goodwill Calculation

Determining goodwill involves a straightforward process, though it hinges on accurately assessing the fair value of the acquired entity. The calculation hinges on subtracting the fair value of the identifiable net assets from the purchase price. The purchase price, essentially the cost of acquiring the entity, includes all direct and indirect costs associated with the acquisition. Fair value of identifiable net assets are the fair value of the acquired entity’s assets and liabilities excluding the intangible assets that are not separately identifiable.

Goodwill = Purchase Price – Fair Value of Identifiable Net Assets

Impairment Testing Procedures

Impairment testing for goodwill involves a systematic process to ensure its carrying amount isn’t higher than its recoverable amount. The recoverable amount is the higher of the fair value less costs to sell and value in use. This assessment is essential to prevent overstating assets on the balance sheet.

- Step 1: Assess the Existence of Impairment Indicators: Indications that goodwill might be impaired include significant changes in the economic conditions of the acquired entity, such as a downturn in the market, or strategic shifts that negatively impact future cash flows.

- Step 2: Determine the Fair Value or Value in Use: Determining the recoverable amount involves either estimating the fair value less costs to sell, or calculating the value in use, which estimates the present value of the future cash flows generated by the acquired entity. This step requires meticulous analysis of the acquired entity’s operations and projected performance.

- Step 3: Comparing Carrying Amount and Recoverable Amount: The carrying amount of goodwill is compared to the recoverable amount. If the recoverable amount is lower, an impairment loss is recognized. The difference between the carrying amount and the recoverable amount is recognized as an impairment loss.

Impairment Loss Calculation

The impairment loss is calculated by subtracting the recoverable amount from the carrying amount of the goodwill. This difference is recognized as an expense in the income statement.

Impairment Loss = Carrying Amount of Goodwill – Recoverable Amount

Impairment Testing Steps Summary

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Assess for impairment indicators. |

| 2 | Determine fair value or value in use (higher of the two). |

| 3 | Compare carrying amount and recoverable amount. |

| 4 | Recognize impairment loss (if necessary). |

Non-Controlling Interests

In a business combination, the acquirer often doesn’t own 100% of the target company. This means there are other shareholders who retain a portion of ownership. These minority interests, or non-controlling interests (NCI), represent a stake held by parties other than the acquiring entity. Understanding how to account for and present NCI is crucial for accurate consolidated financial reporting.

Accounting Treatment of Non-Controlling Interests

The accounting treatment of non-controlling interests is consistent with the general principle of consolidating the financial statements of the acquired entity. The acquirer records its share of the net assets of the acquired entity at fair value, including the NCI. However, the NCI’s interest is not consolidated at the fair value of the shares, but rather is recorded at the fair value of the net assets attributable to the non-controlling interest at the acquisition date.

Calculation of Non-Controlling Interest Share in Net Assets

Calculating the non-controlling interest’s share in the net assets involves determining the proportion of the target company’s net assets held by the non-controlling interest. This is usually done by applying the percentage of non-controlling interest to the total net assets of the acquired entity.

Example: If a company acquires 80% of another company, the non-controlling interest is 20%. If the target company’s net assets total $100,000, the non-controlling interest’s share would be $20,000 (20% of $100,000).

Presentation of Non-Controlling Interests in Consolidated Financial Statements

Non-controlling interests are presented separately in the consolidated balance sheet, usually as a single line item. The presentation clearly distinguishes the NCI from the equity of the controlling interest. The income statement reflects the NCI’s share of the acquired entity’s net income or loss.

Method for Calculating Non-Controlling Interests

A systematic approach to calculating NCI is essential for accurate reporting. Here’s a step-by-step process:

- Determine the Percentage of Non-Controlling Interest: Calculate the percentage of the acquired entity’s ownership held by parties other than the acquiring entity. This is usually based on the number of outstanding shares held by non-controlling parties divided by the total number of shares outstanding.

- Identify the Net Assets of the Acquired Entity: Gather the net assets of the acquired entity from its financial statements as of the acquisition date. This includes assets, liabilities, and equity.

- Calculate the Non-Controlling Interest’s Share: Multiply the percentage of non-controlling interest by the total net assets of the acquired entity. This is the NCI’s share in the net assets.

- Record in Consolidated Financial Statements: Include the calculated NCI amount as a separate line item in the consolidated balance sheet. The income statement reflects the NCI’s share of the acquired entity’s income or loss.

Consolidation Procedures

The IFRS Business Combinations standard mandates the consolidation of acquired entities’ financial statements with the acquirer’s. This process, often complex, is crucial for providing a holistic view of the combined entity’s financial performance and position. Accurate consolidation ensures investors and stakeholders have a complete picture of the merged business.

Consolidation Adjustments

Consolidation requires adjustments to align the acquired entity’s financial statements with the acquirer’s reporting framework. These adjustments are vital for presenting a unified financial picture of the combined entity. Several key adjustments are required.

- Elimination of Intercompany Transactions: Transactions between the acquirer and the acquired entity must be eliminated to avoid double-counting. This includes sales, purchases, and intercompany loans. For example, if Company A sells inventory to Company B (its subsidiary), the sale and related cost of goods sold must be eliminated in the consolidated financial statements. This prevents inflating reported revenue and expenses.

- Adjusting for Differences in Accounting Policies: If the acquired entity uses accounting policies different from the acquirer’s, the financial statements need adjustments to ensure comparability. For instance, if the acquired entity uses a different depreciation method, the depreciation expense must be recalculated using the acquirer’s policy. This ensures consistency in the consolidated reporting.

- Recognizing Non-Controlling Interests: The portion of the acquired entity not held by the acquirer is represented as non-controlling interest (NCI). This interest needs to be reflected in the consolidated financial statements. For instance, if Company A acquires 80% of Company B, the remaining 20% is NCI and must be separately accounted for in the consolidated statements.

- Adjusting for the Acquisition Date: The acquired entity’s financial statements need to be adjusted to reflect the acquisition date. This involves converting any interim statements to a comparable period to the acquirer’s reporting period.

Preparation of Consolidated Financial Statements

The consolidated financial statements encompass the combined financial information of the acquirer and the acquired entity. The process involves combining the respective balance sheets, income statements, cash flow statements, and statements of changes in equity.

- Combining Balance Sheets: Assets and liabilities of the acquirer and acquired entity are combined. Significant consolidation adjustments, like intercompany balances and differences in accounting policies, are incorporated.

- Combining Income Statements: The combined income statement reflects the consolidated revenue, expenses, and net income of the combined entity. Intercompany transactions are eliminated. Non-controlling interests (NCI) are accounted for separately.

- Preparing Consolidated Cash Flow Statements: Cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities of the acquirer and acquired entity are combined. Intercompany transactions are adjusted to avoid double counting. Adjustments for NCI are also necessary.

- Preparing Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity: The statement details the changes in equity for the consolidated entity. NCI is accounted for separately.

Consolidation Process Flowchart

The consolidation process can be visually represented as a flowchart, outlining the sequential steps involved.

A flowchart would visually display the process beginning with the identification of the acquisition, moving through the adjustments, combination of statements, and ultimately ending with the presentation of consolidated financial statements.

Practical Applications and Examples

Putting the IFRS Business Combinations Standard into practice requires understanding how companies combine with each other. This section provides practical examples and scenarios to illustrate the application of the standard, showcasing how companies identify, measure, and account for these transactions. From real-world mergers to hypothetical acquisitions, these illustrations highlight the complexities and nuances of the standard.

Case Study: ABC Company Acquires XYZ Corporation

ABC Company, a leading manufacturer of consumer electronics, decided to acquire XYZ Corporation, a smaller but rapidly growing supplier of innovative components. The acquisition allowed ABC to gain access to XYZ’s cutting-edge technology and secure a crucial supply chain. Applying the IFRS standard, ABC needed to identify and measure the acquisition costs, including purchase price, transaction costs, and any contingent liabilities.

They then had to assess control over XYZ, which, after the acquisition, was transferred to ABC. This transfer of control is crucial for determining whether the combination should be accounted for as a purchase or a pooling of interests. Intangible assets acquired, such as patents and trademarks, were recognized and valued separately. The difference between the purchase price and the fair value of the identifiable net assets acquired represents goodwill.

ABC had to determine if this goodwill was impaired, and if so, to write down its value.

Real-World Example: The Merger of TechGiant and Innovate

The merger of TechGiant and Innovate demonstrates the complexities of a business combination. TechGiant, a global technology leader, acquired Innovate, a start-up specializing in artificial intelligence. This combination aimed to leverage Innovate’s innovative technology to enhance TechGiant’s existing product line. The IFRS standard dictates the evaluation of Innovate’s identifiable net assets and the recognition of any goodwill or impairment.

The integration of Innovate’s operations into TechGiant’s existing structure was complex, demanding careful consideration of the fair value of identifiable net assets and the potential impact on the consolidated financial statements. Non-controlling interests of Innovate were also accounted for in the financial statements. Accurate identification and measurement of these non-controlling interests is critical to the overall accounting process.

Scenario: A Merger or Acquisition

Consider a scenario where “MegaCorp” acquires “MiniCorp”. MegaCorp, a large retail chain, acquires MiniCorp, a smaller online retailer. MegaCorp pays $10 million for MiniCorp, which includes $1 million in transaction costs. MiniCorp’s identifiable net assets are valued at $8 million.

| Item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Purchase Price | $10,000,000 |

| Transaction Costs | $1,000,000 |

| Identifiable Net Assets | $8,000,000 |

| Goodwill | $3,000,000 |

The $3 million difference represents goodwill, which is an intangible asset. The consolidation process will incorporate MiniCorp’s financial statements into MegaCorp’s consolidated financial statements. The non-controlling interest, if any, will be reported separately.

Scenario Illustrating the Application of the Standard

Imagine a scenario where “Software Solutions” acquires “Data Analytics”. Software Solutions, a software company, acquires Data Analytics, a data analytics company. The purchase price is $50 million, with identifiable net assets valued at $40 million. Transaction costs are $2 million.

| Item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Purchase Price | $50,000,000 |

| Transaction Costs | $2,000,000 |

| Identifiable Net Assets | $40,000,000 |

| Goodwill | $12,000,000 |

This scenario demonstrates the calculation of goodwill and highlights the need for accurate valuation of identifiable net assets. The accounting treatment for goodwill and non-controlling interests will significantly impact the consolidated financial statements of Software Solutions.

Recent Amendments and Updates

The IFRS Business Combinations Standard, while foundational, is a dynamic framework. Continuous improvements and amendments ensure its relevance in a changing business landscape. These updates often reflect evolving accounting practices and address specific issues identified through practical application and analysis. This section details key recent changes, their rationale, and impact on financial reporting.

Amendments to the Definition of Control

Recent amendments to the standard have clarified the definition of control in a business combination. The previous standard lacked specific guidance on certain scenarios, leading to inconsistent interpretations and application. The revised standard now explicitly addresses situations involving significant influence, joint control, and the impact of contractual provisions on the assessment of control. This enhanced clarity allows for more precise identification of control and a more consistent approach across different transactions.

Impact on Financial Reporting

The amended definition of control directly impacts the accounting treatment of business combinations. For example, a transaction previously deemed a mere investment might now be recognized as a controlling interest, requiring consolidation in the financial statements. Conversely, a transaction previously requiring consolidation might now be accounted for as an investment due to a change in the control definition.

These adjustments ensure financial statements accurately reflect the economic substance of business combinations.

Comparison of Previous and Current Standards

The previous standard lacked specific guidance on scenarios like significant influence, joint control, and contractual provisions. This often led to differing interpretations and accounting treatments across different jurisdictions. The current standard addresses these gaps by providing clear definitions and guidance, promoting consistency and comparability in financial reporting. A key change is the explicit recognition of the importance of contractual agreements in assessing control.

This allows for a more nuanced understanding of the economic rights and obligations associated with a business combination. The enhanced clarity in the current standard translates into more accurate and reliable financial reporting.

Examples of Practical Applications

Consider a company acquiring a subsidiary where the acquisition agreement includes a provision granting the acquirer significant influence over the subsidiary’s operating decisions. Under the previous standard, this might have been challenging to quantify. The current standard provides clearer criteria to assess if the significant influence translates into control, enabling more accurate recognition of the acquisition’s impact. Another example involves a joint venture where the contractual agreements define the level of influence each party has.

The revised standard provides a framework for assessing control based on the specific contractual obligations, ensuring consistent accounting treatment.

Final Review

In conclusion, the IFRS business combinations standard provides a robust framework for accounting for business combinations. This standard, while complex, is vital for accurate and transparent financial reporting. Navigating its intricacies can be challenging, but this guide provides a solid foundation for understanding its principles and applications. By meticulously following the steps and considering the nuances, stakeholders can ensure accurate and reliable financial reporting in their transactions.

FAQ Explained

What is the difference between a merger and an acquisition?

A merger is when two companies combine to form a new entity, while an acquisition is when one company buys another. The IFRS standard applies to both scenarios.

How is goodwill calculated?

Goodwill is the excess of the purchase price over the fair value of the identifiable net assets acquired. The specific method for calculation is detailed in the standard.

What are the common indicators of control in a business combination?

Common indicators of control include the ability to direct the activities of the acquired entity, power to obtain the benefits from the acquired entity, and the ability to affect the entity’s significant economic returns.

How often does the IFRS standard for business combinations get updated?

IFRS standards are subject to periodic review and updates to reflect evolving business practices and economic conditions. The frequency of updates varies but is typically regular.